A Plaster Cast Pact

There was a time when 77 soulless bodies lived in Ireland’s National Museum of Art. There in the entrance hall stood these statues, daring you to investigate whether or not their marble registers your finger the same way a pillow does. Their bodies seem to carry more life than us, similar to how I can miss a memory more than the experience behind it.

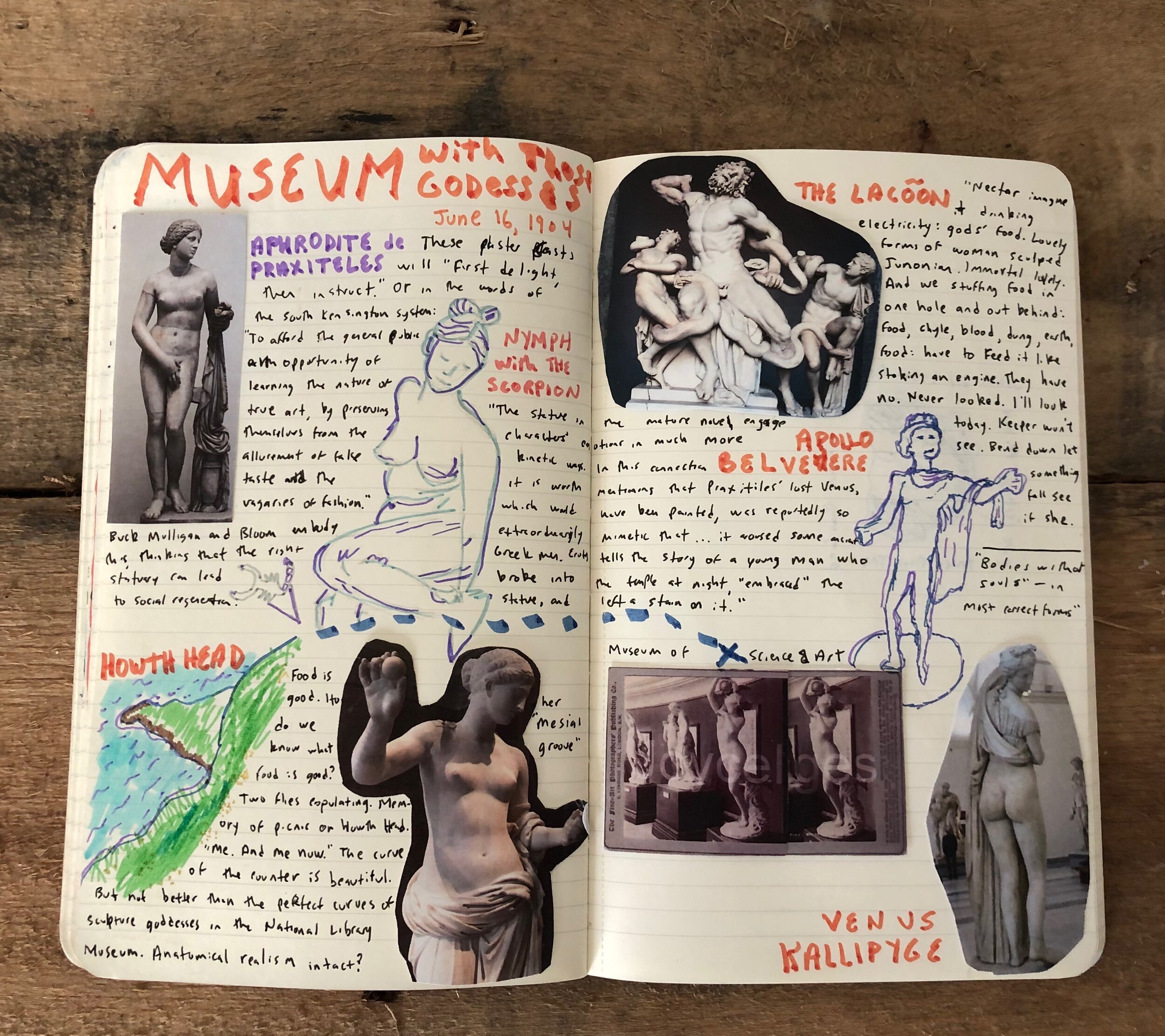

Statues like Ireland’s appeared in many welcome rotundas. Nineteenth-century museums were worried visitors would be overwhelmed with contemporary artwork and feel dumb, so they staged these Greco-Roman statues (plaster cast replicas, actually) in their entries, saying that such a display of classical work would ground visitors in true art before they encountered newer work. The statues would “first delight, then instruct,” they said, preserving the public from the sway of fashion. So Ireland was thrilled when Antonio Canova sculpted a batch of statues as a gift for their museum. The Borghese Gladiator, Laocoon, Apollo, Venus—all these Canova sculpted, pounds and pounds of marble flesh in the image of God, no, even better, in his own image, they have wrinkled hands you can hold and fat on their sides and bellies. That Canova carved these flaws into the marble bodies makes them no less what we would consider a human flaw. More human than God, and better for it.

So at the heyday of these fake-marble gods and goddesses, there’s this fictional character, Leopold Bloom, sitting at lunch in the world James Joyce has plunged him into in Ulysses. As he eats, Bloom thinks about how graceful the food must be that statues eat: “Shapely goddesses, Venus, Juno: curves the world admires. . . . Nectar imagine it drinking electricity: gods’ food. . . . And we, stuffing food in one hole and out behind: food, chyle, blood, dung, earth, food.” Bloom notices two flies on top of each other and remembers a picnic with his wife at Howth Head, and then notices how nice the curves of the oak countertop are, reminding him of one of the statues’ ass on display in the museum. And then a question: do statues have anuses? “They have no. Never looked. I’ll look today. Keeper won’t see. Bend down let something fall see if she.” Good question.

What a book this was, this epic of the body. Ulysses is a book embracing our everyday humanity, like the brine under our fingernails, the smells of a city street, a mid-lunch visit to a public toilet. This is the same ooze King Krule croons about into your speakers when you ask him to. This embrace of the dirt gives you new eyes through which to see an average day. As I read, I kept wondering what parts of my day and all its salt and oil would show up in its pages. I once heard a professor say he has a friend who only reads Ulysses in his old age because he wants to spend whatever time he has left with masterpieces.

So Bloom rushes to see the statue’s figure. It’s hard to tell exactly which statues would’ve been in the room when Bloom made his fictitious trip to the museum with those goddesses on June 16, 1904, but there’s really only one that matters. He makes right for the Venus Kalipge, whose name means “Venus with the beautiful buttocks.” He checks to make sure no one’s looking before stealing a glance to where her anus should be. With this one movement, Bloom hilariously and unknowingly undercuts the museum’s goal—some people can’t be guided to lofty thoughts, even when looking beauty in the eye. There they were, timeless masterpieces these statues, strategically placed by someone smarter than Bloom trying to connect him to history, to form, to beauty. Instead, he looks for an asshole.

But my favorite part is that maybe Bloom was moved by a higher beauty. Even if the statues were placed there as a mind-control tactic, Bloom recognizes statues as vehicles of the real. In Venus, he recognizes his own body.

Maybe not, but maybe Bloom felt in his very skin the idea that statues are almost more human than human. They don’t come from evolution or God or the great chain of being or whatever you believe in, that doesn't’ matter right now. When someone sculpts, a human mind is projecting what it sees into marble—five feet of pure feeling, pulled out of the artist and standing next to them. And they’re also pliable to viewers’ emotions; if I were to translate a statue from marble to paper, it wouldn’t have eyes, just empty circles ready to hold any feeling I want it to. It’s like the scene in Titus where the boy runs into the workshop and sees all the wooden figures. After he’s just seen hands and heads separated from their bodies in the scene before, the wooden bodies seem to be watching, threatening to turn him into wood too. They are bodies that feel simultaneously familiar and ghostly, like hearing words your lover said to you repeated by a child. What’s the difference between real hands, severed hands, wood-carved hands, movie prop hands? “These heads seem to be talking to me,” Titus says, holding the lifeless heads of his sons. And they seem to be saying more than they did when they were living.

This weekend, Sara and I visited my parents a half-hour east of Columbus. After a day of hiking, we ended the day by listening to a pair of new singles in the quiet of my old room. When the music stopped and we both laid there for a while, the phone still resting on my chest. I felt proud for a moment that I didn’t fill the silence with my opinion of the music. I’ve been trying to let silence fill the gaps on either side of a new experience more often so that I can slow down and absorb it. I used to be silent for different reasons—when I was in college and we’d go to the Art Institute or listened to new music on drives, I wouldn’t say anything right away out of fear of saying something stupid, afraid I’d fill the precious shapeless moments after a transforming experience with my words when one of my friends probably had a readier bit of truth to share with the group. I realize now (and knew deep down then, probably) that this is not how friendships should work—they cared enough about me that they would’ve loved to hear my thoughts.

But as we laid there in the wake of the songs, I realized that Sara’s always been good at this practice of silence. Her silence comes not out of fear, but because she wants to spend time with her feelings. For me, instead of considering what I feel first, it’s easy for me to encounter new things by trying to get through them, worried about how I’ll be viewed and not how I see things. Instead of working out my feelings in something I make, I worry what making that thing says about me. When did I stop looking for what’s real?

Yeah, Bloom was probably the butt of Joyce’s joke for being so one-dimensional. But for me, Bloom’s abandon has sort of become a totem for following your curiosity. He was there for what’s real. He was there for the human part of it. Ignoring your curiosity for what’s real or human doesn’t make it any less real. Maybe this is what Durga Chew-Bose means when she talks about appraising what naturally heaps in you, that strange soreness inside. So I say look for the asshole.